13 min read

The Ins and Outs of Anchoring Bias Marketing

Jeremy Wayne Howell

:

Jan 17, 2026 10:41:13 AM

Why Your 'Perfect' Price Is a Shot in the Dark

Anchoring bias marketing is the strategic use of an initial reference point—like a higher price, a competitor's rate, or a specific number—to influence how customers perceive value and make purchasing decisions. It works because the human brain relies heavily on the first piece of information it encounters, even when that information is arbitrary or irrelevant.

Quick Answer: What You Need to Know

- What it is: A cognitive bias where the first number you see becomes the mental benchmark for all subsequent judgments

- Why it matters: It directly affects customer perception of value, pricing decisions, and conversion rates

- How it works: The brain "anchors" to initial information and makes insufficient adjustments away from it

- Where it's used: Pricing pages, sales negotiations, discounts, product tiers, and advertising

- Ethical line: Using anchoring to highlight genuine value is persuasive; using it to create false perceptions is manipulative

You've probably experienced this yourself. You walk into a store planning to spend $50, see a jacket marked down from $200 to $120, and suddenly $120 feels like a steal—even though you never intended to spend that much. Or you're comparing software plans, and the $500/month option makes the $200/month tier look perfectly reasonable, even though $200 still stretches your budget.

That's not random. That's anchoring bias at work.

The problem is most businesses use anchoring accidentally—or not at all. They set prices based on cost-plus formulas, competitor averages, or gut feel. They present options in random order. They discount without context. And then they wonder why customers hesitate, negotiate aggressively, or choose the cheapest option by default.

The research is clear: when Campbell's Soup added a "Limit 12 cans per person" sign during a sale, purchases jumped from 3.3 cans to 7 cans per shopper—a 112% increase. When Williams-Sonoma introduced a $429 bread maker, sales of their original $275 model skyrocketed. KFC Australia's "A deal so good you can only buy four" campaign drove a 56% sales increase.

These aren't flukes. They're the result of understanding how the human brain processes value.

But here's what most marketing content won't tell you: anchoring isn't just a pricing trick. It's a window into how your customers think, what they believe is reasonable, and where their uncertainty lives. When you ignore it, you're letting random factors—like whatever number they saw last, or a competitor's arbitrary price—set the anchor for you. When you design for it, you guide perception, reduce decision friction, and build trust.

I'm Jeremy Wayne Howell, founder of The Way How, and over the past 20+ years I've helped companies grow from early traction to $1M+ ARR by aligning marketing and sales around buyer psychology—including how anchoring bias marketing shapes pricing, messaging, and negotiation outcomes. This guide will show you how anchoring works, why it matters, and how to apply it ethically and effectively in your own revenue system.

Anchoring bias marketing terms you need:

The First Number Wins: Understanding the Psychology of Anchoring

We make thousands of decisions every day—an estimated 35,000 for the average adult. To steer this constant barrage of choices, our brains rely on mental shortcuts called heuristics. These heuristics, while efficient, can sometimes lead us astray, introducing biases into our decision-making. One of the most pervasive of these is anchoring bias.

The concept of anchoring bias, or the anchoring effect, first gained widespread recognition through the groundbreaking work of psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. Their scientific research on judgment under uncertainty in the 1970s revealed how powerfully an initial piece of information—even an arbitrary one—can influence subsequent judgments. This phenomenon is a cornerstone of behavioral economics and has profound implications for understanding human decision-making, particularly in marketing.

What is Anchoring Bias and How Does It Work?

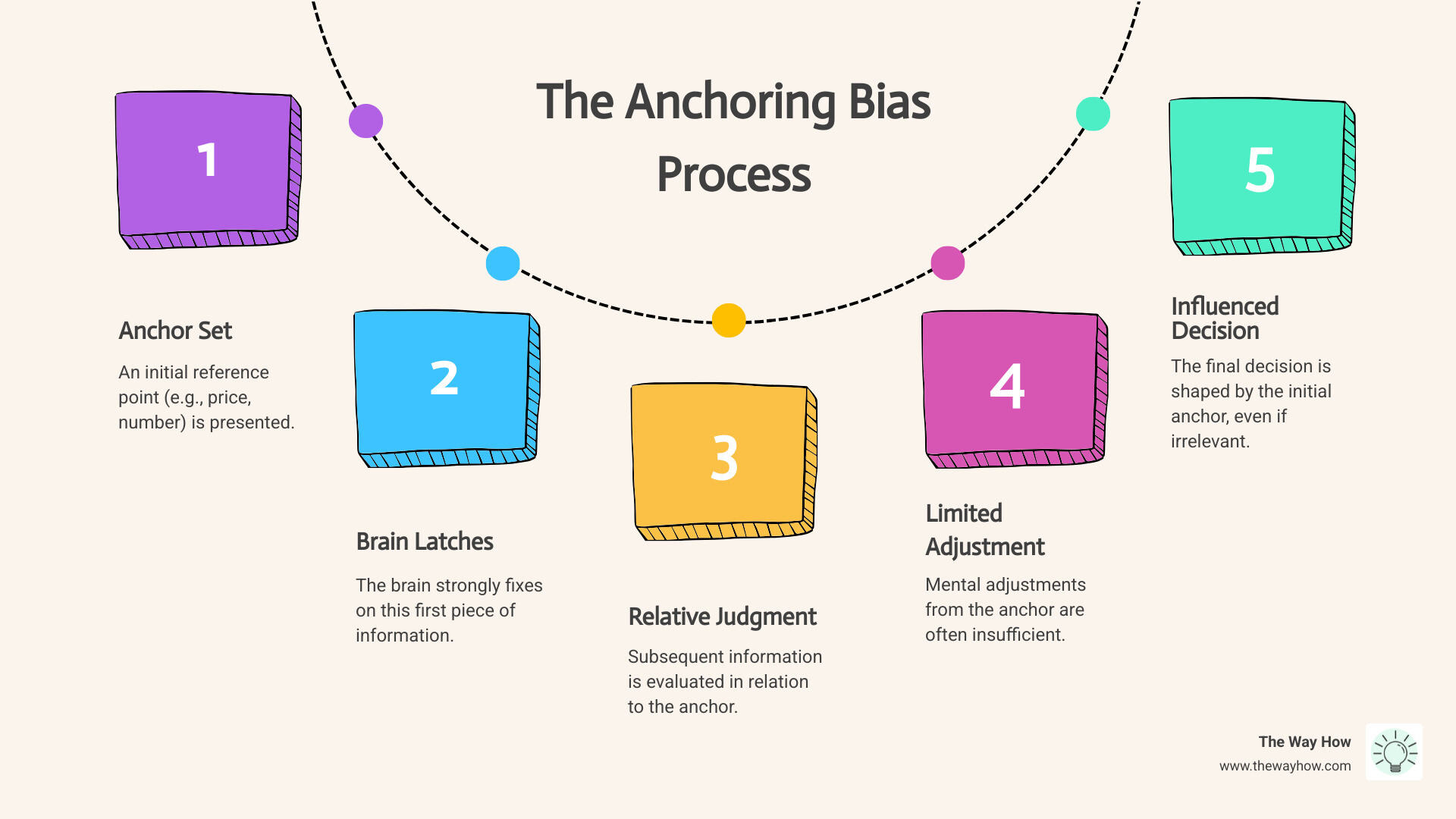

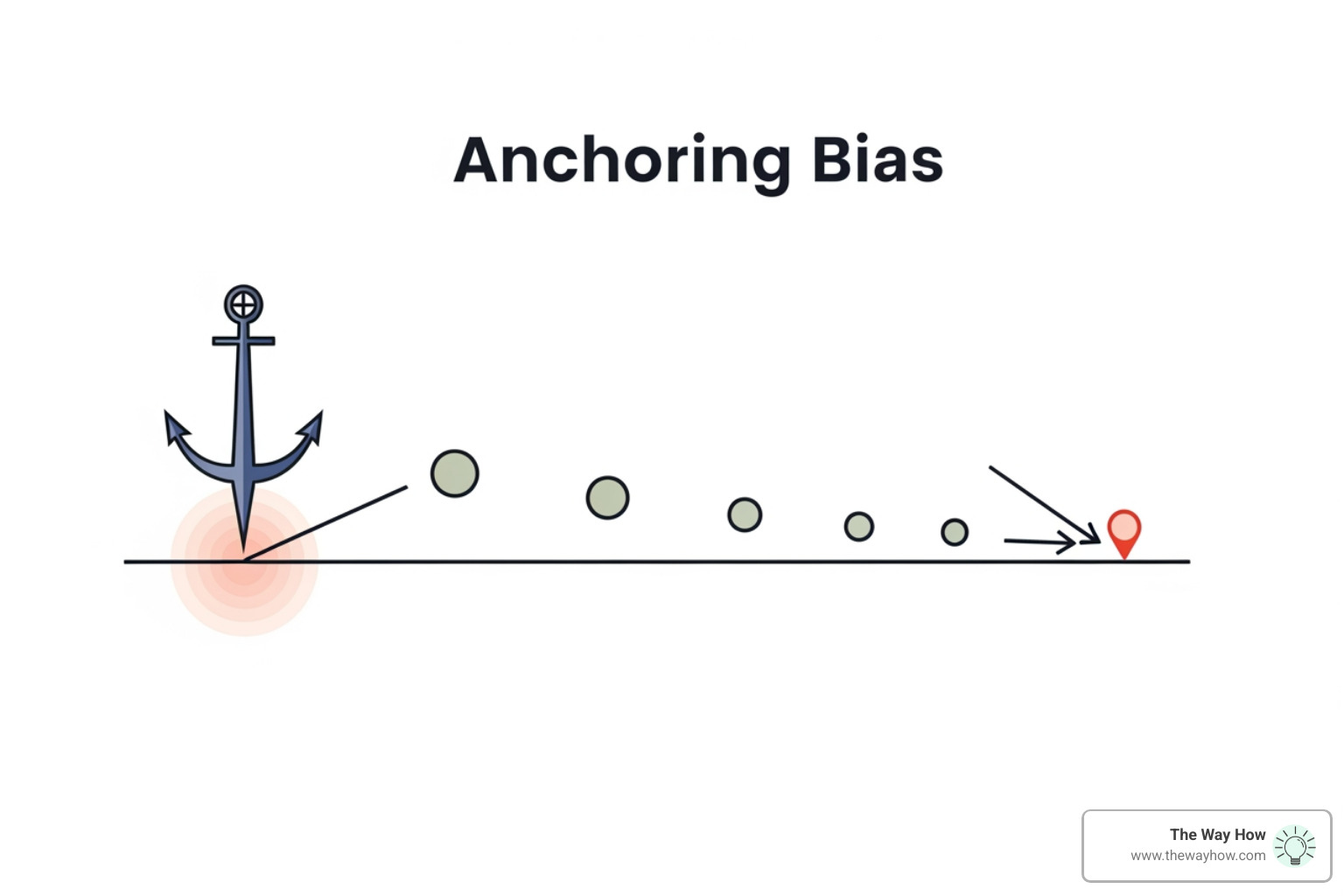

Anchoring bias describes our tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information we encounter (the "anchor") when making decisions. This initial reference point then disproportionately influences our subsequent judgments, even if it's irrelevant to the decision at hand. We tend to value this first piece of information over later, more pertinent data, often leading to less rational choices.

Think of it like this: your brain grabs onto the first number it sees and then, when presented with other numbers, it tries to adjust from that initial point. The problem is, these adjustments are usually insufficient, leaving your final decision skewed towards that first anchor.

Tversky and Kahneman famously demonstrated this with their "wheel of fortune" experiment. Participants were asked to estimate the percentage of African countries that were members of the United Nations. Before giving their estimate, they spun a rigged wheel that would land on either 10 or 65. Those who saw the wheel land on 10 gave a median estimate of 25%, while those who saw 65 gave a median estimate of 45%. Despite knowing the number from the wheel was random, it significantly anchored their subsequent estimates. This illustrates precisely how anchoring bias works: an arbitrary initial number sets an expectation, and our adjustments from that anchor are simply not enough.

The Hidden Mechanics: Why Our Brains Get Stuck

So, why do our brains get stuck on that first number? Psychologists have proposed several mechanisms:

- The Anchor-and-Adjust Hypothesis: This is the most direct explanation. We start with the anchor and then attempt to adjust our estimate or decision away from it. However, we typically stop adjusting too soon. As one paper suggests, once a plausible answer is reached, we may cease further adjustment, leaving us closer to the initial anchor than we should be.

- Selective Accessibility Theory: This theory suggests that anchors selectively make information consistent with the anchor more accessible in our minds. If the anchor is high, we're more likely to retrieve and consider arguments or features that support a higher value.

- Primacy Effect: Similar to how we often remember the first items in a list better than those in the middle, the primacy effect suggests that the initial information (the anchor) is simply more salient and memorable, thus exerting a stronger influence.

- Attitude Change from an Initial Value: Some psychologists believe that the first piece of information can cause a shift in our attitude or perception of what is likely to be correct. We begin to believe that answers similar to the initial value are more probable, leading us to seek out and favor attributes that align with that initial perception.

Anchoring vs. Other Mind Games

While anchoring bias is a powerful cognitive shortcut, it's not the only one. It often works in conjunction with or is confused with other biases that influence our decisions. Understanding the distinctions helps us diagnose the true drivers of behavior.

| Bias | Definition | How it Differs from Anchoring |

|---|---|---|

| Anchoring Bias | Over-reliance on the first piece of information (the "anchor") when making decisions, leading to insufficient adjustments. | Focuses on the initial numerical or informational reference point that skews subsequent judgments. |

| Framing Effect | Decisions are influenced by how information is presented or "framed," rather than by the objective facts. | Deals with the presentation of information (e.g., 90% fat-free vs. 10% fat) and how it shifts perception, not an initial number. |

| Halo Effect | A positive impression of a person, company, or product in one area positively influences our feelings in other areas. | Relates to general positive or negative impressions spreading across different attributes, not a specific initial data point. |

For a deeper dive into how presentation can shape perception, explore our Marketing framing effect guide.

Other related biases often seen alongside anchoring include:

- Decoy Effect: Introducing a strategically inferior "decoy" option to make a target option seem more attractive (e.g., the Economist example we'll discuss soon).

- Endowment effect marketing: We tend to value things we own more highly than identical items we don't own.

- Loss Aversion: Our tendency to prefer avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains.

These biases, while distinct, frequently interact to subtly guide our choices, highlighting the complexity of human decision-making.

Factors That Strengthen or Weaken the Anchor

While anchoring is robust, its influence isn't uniform. Several factors can either amplify or mitigate its effect:

- Group Dynamics: Surprisingly, when a group tackles a problem involving anchoring bias, the bias has less impact on their collective decisions. Research has shown that each person brings their own "internal anchors"—individual reference points based on beliefs, experiences, or context—which compete and balance out within the group, leading to a more moderate outcome.

- Business Intelligence: Even sophisticated business intelligence (BI) systems, which are designed to provide comprehensive data analysis for better forecasting, can fall prey to anchoring. If a plausible anchor is initially presented, even a system designed for objectivity can be subtly influenced, reinforcing the need for critical human oversight.

- Mood and Personality: Our emotional state can play a role. Studies have shown that people in a more positive mood are generally less affected by anchoring bias, even though sadder moods often lead to more accurate estimates in other contexts. Similarly, research based on the "big five" personality traits suggests that agreeable, open-minded, and more neurotic individuals might be less susceptible to anchor bias compared to conscientious or extroverted individuals.

- Expertise and Knowledge: While knowledge is power, it doesn't grant immunity. Studies indicate that being knowledgeable about a subject can lessen the anchoring effect, but experts will still be susceptible. Even doctors, for instance, can fall victim to anchoring bias by relying too heavily on the first piece of information they receive about a patient, potentially leading to an incorrect diagnosis.

Anchoring in the Wild: Real-World Examples You See Every Day

Once you understand anchoring bias, you start seeing it everywhere. From the supermarket aisle to the car dealership, marketers and salespeople consciously or unconsciously leverage this cognitive shortcut to influence our perception of value and ultimately, our purchasing behavior.

Retail and Pricing Strategies

This is perhaps the most common battleground for anchoring bias marketing.

- The Williams-Sonoma Bread Maker: A classic example. When Williams-Sonoma introduced a high-end bread maker priced at $429, sales of their original $275 model significantly increased. The $429 model served as an anchor, making the $275 machine seem like a reasonable, mid-range option by comparison.

- The Economist Subscription: Behavioral economist Dan Ariely famously described this experiment in his book "Predictably Irrational." The Economist offered three subscription options:

- Online-only: $59

- Print-only: $125 (the decoy/anchor)

- Print & Online: $125 When all three were offered, 84% chose the Print & Online bundle. When the print-only option was removed, fewer chose the combined bundle, and more opted for the cheapest online-only option. The $125 print-only option served as a powerful anchor, making the identical-priced bundle seem like an incredible deal.

- Prices Ending in ".99": We're all aware of the ".99" trick, yet it still works. Studies show that prices ending in ".99" can lead to 50-100% higher purchase likelihood compared to rounded prices, even for a one-cent difference. Our brains anchor to the first digit, making $4.99 feel much closer to $4 than $5. As research from Ohio State University demonstrated, even though we intellectually know $4.99 is essentially $5, our brains anchor to the '4', giving the impression of a better deal.

- "Was/Now" Pricing: Retailers constantly use this strategy. They display an original, higher price (the "Was" price) crossed out next to a lower, discounted price (the "Now" price). This sets a high anchor, making the current price seem like a significant saving. However, as Shopify and Forbes report, this can be deceptive if the item was rarely, if ever, sold at the "original" price, which we'll discuss in ethics.

Purchase Quantity and Perceived Scarcity

Anchors don't always have to be about price. They can influence how much we think we should buy.

- Campbell's Soup "Limit 12" Sign: This is a stellar example of how quantity limits can serve as anchors. When Wansink, Kent, and Hoch tested their theory with cans of Campbell’s soup, they found that when a "Limit 12 cans per person" sign was added, purchases increased from an average of 3.3 cans to 7 cans per shopper—a remarkable 112% increase. The limit, though seemingly restrictive, established 12 as a reasonable quantity, anchoring shoppers' perception of how much they should buy.

- KFC Australia's "1-Dollar Chips": In 2014, Ogilvy Asia faced the challenge of boosting KFC French Fry sales without changing the product, offer, or price. Their solution? A campaign built around the anchor "A deal so good you can only buy four." This simple phrase, by setting an implicit quantity anchor, resulted in a 56% increase in sales.

High-End and B2B Contexts

Anchoring isn't just for consumer goods; it's a powerful force in high-value transactions and B2B settings too.

- Rolls Royce at Aircraft Shows: As the legendary adman Rory Sutherland once quipped, Rolls Royce stopped exhibiting at car shows and instead exhibited at aircraft shows. Why? Because, as he explains, "If you've been looking at jets all afternoon, a £300,000 car is an impulse buy. It's like putting the sweets next to the counter." The multi-million-dollar jets served as an extreme anchor, making the luxury car seem relatively affordable.

- SaaS Pricing Tiers: Many SaaS companies strategically display their most expensive or "Enterprise" plan first on their pricing pages. This high-priced option acts as an anchor, making the mid-tier "Pro" or "Business" plans seem much more reasonable and value-packed by comparison, nudging customers towards a more profitable option.

- Negotiation Starting Points: In any negotiation, the first number mentioned—whether it's a salary expectation, a project bid, or a sale price—serves as a powerful anchor. The party that sets this initial anchor often tends to do better in the negotiation, as subsequent offers are evaluated relative to that starting point. This is a core principle in neuromarketing techniques for sales.

From Random Tactic to Revenue System: Applying Anchoring Bias Marketing

At The Way How, we believe that understanding human behavior is not about chasing fleeting tactics, but about building predictable revenue systems. Leveraging anchoring bias marketing isn't just a trick; it's a strategic lever for growth marketing, conversion rate optimization, and ultimately, sustainable revenue generation. It's about consciously guiding perception rather than leaving it to chance.

Strategic Applications of Anchoring Bias Marketing in Pricing

Pricing is where anchoring truly shines, and it's a critical component of any well-designed revenue system.

- Tiered Pricing and Premium-First Display: As seen with SaaS companies, presenting your highest-priced, most comprehensive package first establishes a high anchor. This makes your mid-tier options, which are often your sweet spot for profitability, appear more affordable and value-rich. We help founders design these structures to remove uncertainty from the buyer's decision-making process.

- Decoy Pricing: This involves introducing a slightly less attractive, often similarly priced "decoy" option to make your preferred option seem like an obvious choice. The Economist example is a perfect illustration.

- Value Anchoring with Lead Magnets: Even free resources can benefit. By clearly stating the monetary value of a lead magnet (e.g., "Download our Complete Marketing Guide ($199 Value) – Free for a Limited Time"), you anchor its perceived worth, making the free download seem like a significant gain.

- Subscription Models: Highlighting the savings of an annual subscription over a monthly plan (e.g., "Save 20% with an annual plan") anchors the higher monthly cost, making the annual commitment seem like the smarter financial decision.

Leveraging Anchoring Bias Marketing in Sales and Negotiations

In sales and negotiation, the first number on the table often dictates the playing field.

- Setting the First Offer: Whether it's a proposal for a new project or a salary negotiation, making the first offer strategically can be a game-changer. That initial number becomes the anchor, influencing all subsequent counter-offers and the final agreement. As we've noted, the party that sets the first anchor generally tends to do better.

- Discrediting an Opponent's Anchor: What if the other party sets an anchor you don't like? Daniel Kahneman, in this interview with Inc. Magazine, suggests that the best defense is to utterly refute and discredit the number. Assertively denying its credibility helps to wipe it from both your mind and the mind of the other party, allowing for a reset. This is a powerful psychological tactic for maintaining control of the sales process.

Digital Marketing Applications: Google Ads and Landing Pages

Anchoring bias marketing extends seamlessly into the digital field, impacting everything from ad copy to landing page conversions.

- Google Ads Copywriting: Headlines can set powerful anchors. Instead of just stating a price, using "Save X" messaging (e.g., "Save $200 on Professional Website Design (Normally $700)") immediately establishes a high anchor and highlights the perceived gain. We encourage A/B testing ad variations with different anchoring approaches to see what resonates.

- Landing Page Optimization:

- Social Proof Numbers: Beyond pricing, any number can serve as an anchor. Displaying high numbers like "Join 50,000 satisfied customers" or "Increased lead generation by 237% for Company X" (in testimonials) sets an anchor of widespread adoption and significant results, influencing visitor trust and perceived value.

- Form Optimization: Even mundane elements like forms can benefit. Anchoring expectations for completion (e.g., "Just 3 quick questions to get your free quote") can reduce perceived effort and increase conversion rates.

- Tiered Pricing Layouts: For SaaS or service pages, displaying the highest-priced plans on the left (for Western audiences reading left-to-right) ensures the anchor is seen first, influencing the perception of subsequent, lower-priced options.

The Ethical Tightrope: Persuasion vs. Deception

As a psychology-first firm, we believe in using behavioral insights to create trust and momentum, not to manipulate. This means navigating the ethical considerations of anchoring bias marketing with care.

- Misleading "Was" Prices: This is the most common ethical pitfall. When retailers mark up prices only to immediately discount them, it's a deceptive practice. The Washington Post has highlighted how retailers "mark up the prices and then offer seemingly deep discounts to make the deals look more attractive." While deceptive pricing is illegal in the United States, a Consumers’ Checkbook report found it's rarely policed and rampant, with some retailers offering false discounts almost constantly. This erodes consumer trust in the long run.

- False Scarcity: Creating artificial urgency (e.g., "Only 3 left in stock!" when there are hundreds) can be manipulative. While genuine scarcity can be a powerful motivator, false claims damage credibility.

- The JCPenney Cautionary Tale: In 2011, JCPenney's new CEO tried to move away from constant sales and "was/now" pricing to an "everyday low prices" model, inspired by Apple. The result? A massive drop in sales. As Forbes reports, their customers, anchored to the idea of sales, didn't perceive the everyday low prices as good deals. This illustrates the power of consumer expectations and the risk of mismanaging anchors.

Our approach at The Way How is to use anchoring to highlight genuine value, not to create false perceptions. Ethical anchoring bias marketing is about transparency, aligning your pricing with true value differentials, and ultimately building long-term trust and predictable revenue.

Frequently Asked Questions About Anchoring

We often hear similar questions from founders and leadership teams as they grapple with the nuances of buyer psychology. Here are some of the most common:

How can I, as a consumer, avoid falling for anchoring bias?

It's tough, even for those aware of it! But we can take steps to mitigate its influence:

- Be Aware: Simply knowing about anchoring bias is the first defense. Recognize when an initial number might be influencing your judgment.

- Set Your Own Anchor: Before entering a negotiation or viewing prices, determine your own reasonable price or value range. This "pre-anchors" your mind.

- Research Multiple Reference Points: Don't rely on the first price or piece of information you see. Actively seek out comparable products, competitor prices, and market averages to get a broader perspective.

- Delay Decisions: If possible, take time before making a significant purchase or decision. Stepping away can help you evaluate more objectively, rather than acting on an initial, anchored impulse.

- Question Initial Information: Ask yourself: Is this initial number truly relevant? Is it arbitrary? Is it designed to influence me?

Is using anchoring bias in marketing always manipulative?

Absolutely not. We believe there's a clear distinction between persuasion and deception.

- Persuasion: Using anchoring to highlight the genuine value of your product or service, to help customers understand why a higher-tier option offers more benefits, or to clarify savings. This is about making information clearer and guiding a rational decision.

- Deception: Using false "was" prices, creating artificial scarcity, or presenting irrelevant anchors to trick customers into believing they're getting a deal when they're not. This erodes trust and damages your brand long-term.

Ethical anchoring bias marketing is about showing your customer the true value, strategically. It's about designing a customer journey where perceived value aligns with actual value, fostering trust and predictable revenue.

What's the single most effective way to start using anchoring?

If you're looking to integrate anchoring bias marketing into your revenue system, we recommend starting with these practical applications:

- Tiered Pricing with Premium First: On your pricing pages, display your highest-value, highest-priced option prominently first (e.g., on the left for Western audiences). This anchors a high perceived value, making your mid-tier options seem more attractive.

- Honest "Was/Now" Pricing: If you offer discounts, ensure the "Was" price is a legitimate, recent selling price. This builds credibility and makes the discount feel genuine.

- Strategic Negotiation Anchors: In sales conversations, be prepared to set the first offer strategically. Research suggests this significantly influences the outcome.

- Value-Oriented Language: For complex services or products, anchor their value by articulating the return on investment or the problem they solve in quantifiable terms.

Stop Guessing, Start Guiding

We've explored how anchoring bias marketing is far more than a simple pricing trick. It's a fundamental aspect of human psychology that shapes how customers perceive value, make decisions, and ultimately engage with your brand. Ignoring it means leaving your pricing, your sales, and your marketing efforts vulnerable to random external anchors or, worse, to your competitors' strategic use of this bias.

At The Way How, we recognize that the 'perfect' price or the 'optimal' marketing strategy isn't found through guesswork. It's found by deeply understanding customer psychology, diagnosing where uncertainty exists in their decision-making journey, and then designing systems that guide them with clarity and empathy. When you consciously leverage insights like anchoring bias, you move from merely reacting to market conditions to proactively shaping perception, building trust, and creating a truly predictable revenue system.

Ready to stop guessing and start guiding your customers with a psychology-first approach? Build a predictable revenue system with our services.

Want to Learn Something Else?

The Complete Guide to Funnel Optimization